A People’s Vision for Water and Energy

By Lauren Ballesteros-Watanabe, Chapter Organizer | Reading time: 6 minutes

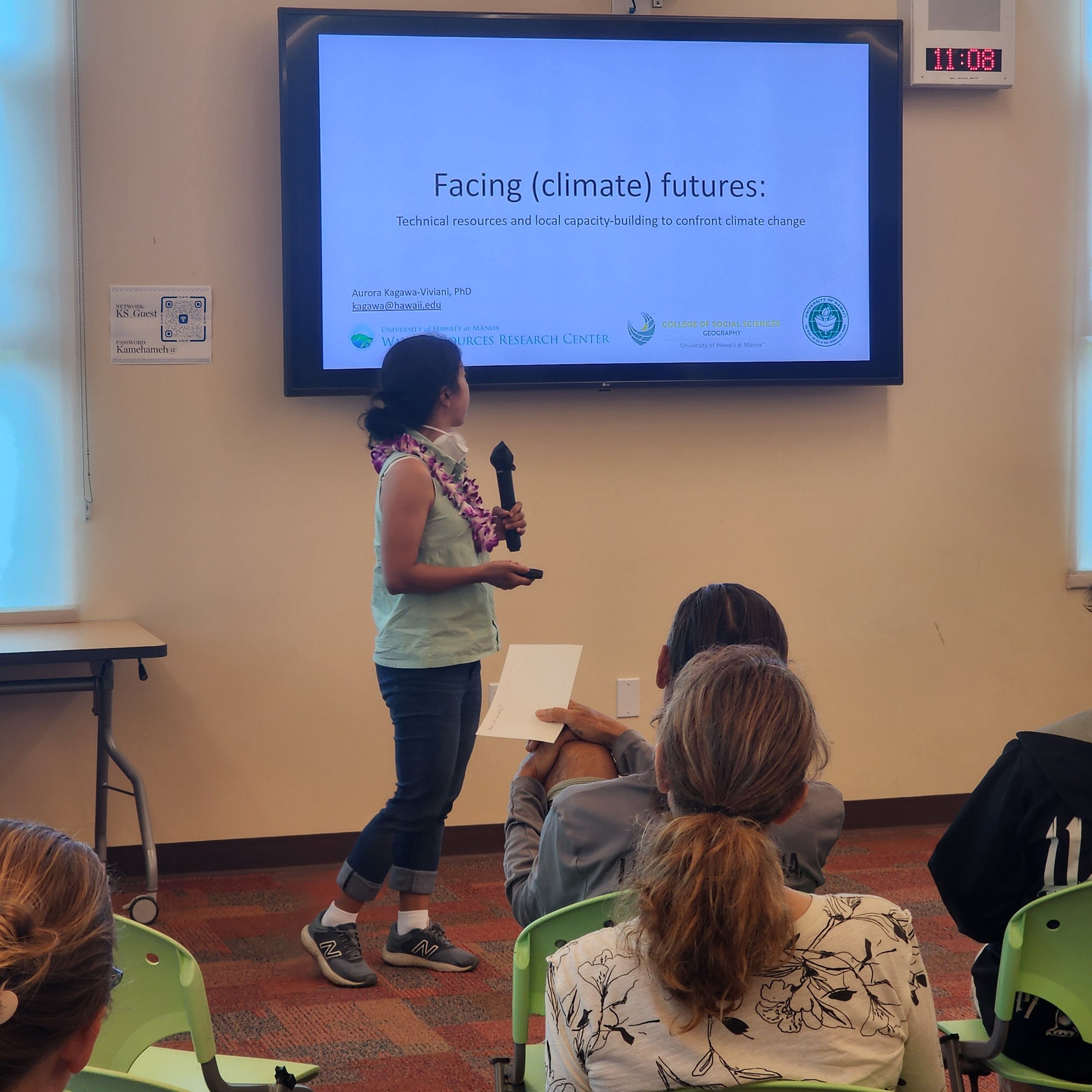

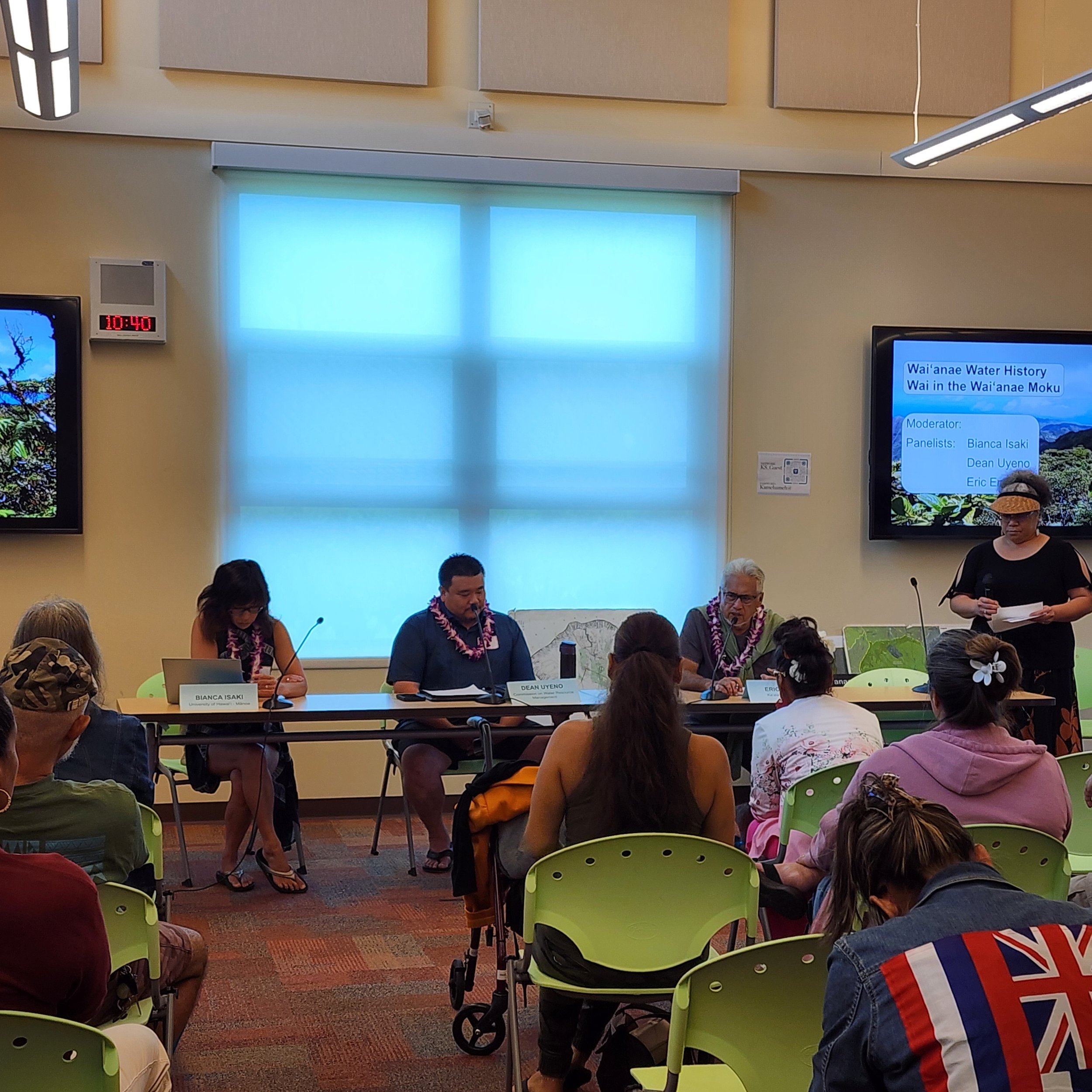

This past month, two critical conversations took place in different communities with the same goal: resource sovereignty. On May 18th, Mohala I Ka Wai, a group dedicated to the preservation, protection, and restoration of water resources, held the Waiʻanae Moku Water Conference as part of the Honolulu Board of Water Supply's "Protecting Wai for Waiʻanae" initiative. A few days later, the Teran James Young Foundation and a grassroots energy advocate hui hosted a community talk-story on how to take back Maui’s energy grid; the event was a grassroots to the annual Hawai’i Energy Conference happening that day.

The conference served as a "launch" to raise awareness of the Board of Water Supply’s current petition to the State Commission on Water Resource Management to designate the Wai‘anae Aquifer Sector Area as a Groundwater Management Area. Without this designation, which already exists for all other aquifers on Oʻahu, any landowner can drill a well and pump groundwater for any use with limited regulatory approvals, regardless of potential detrimental impacts.

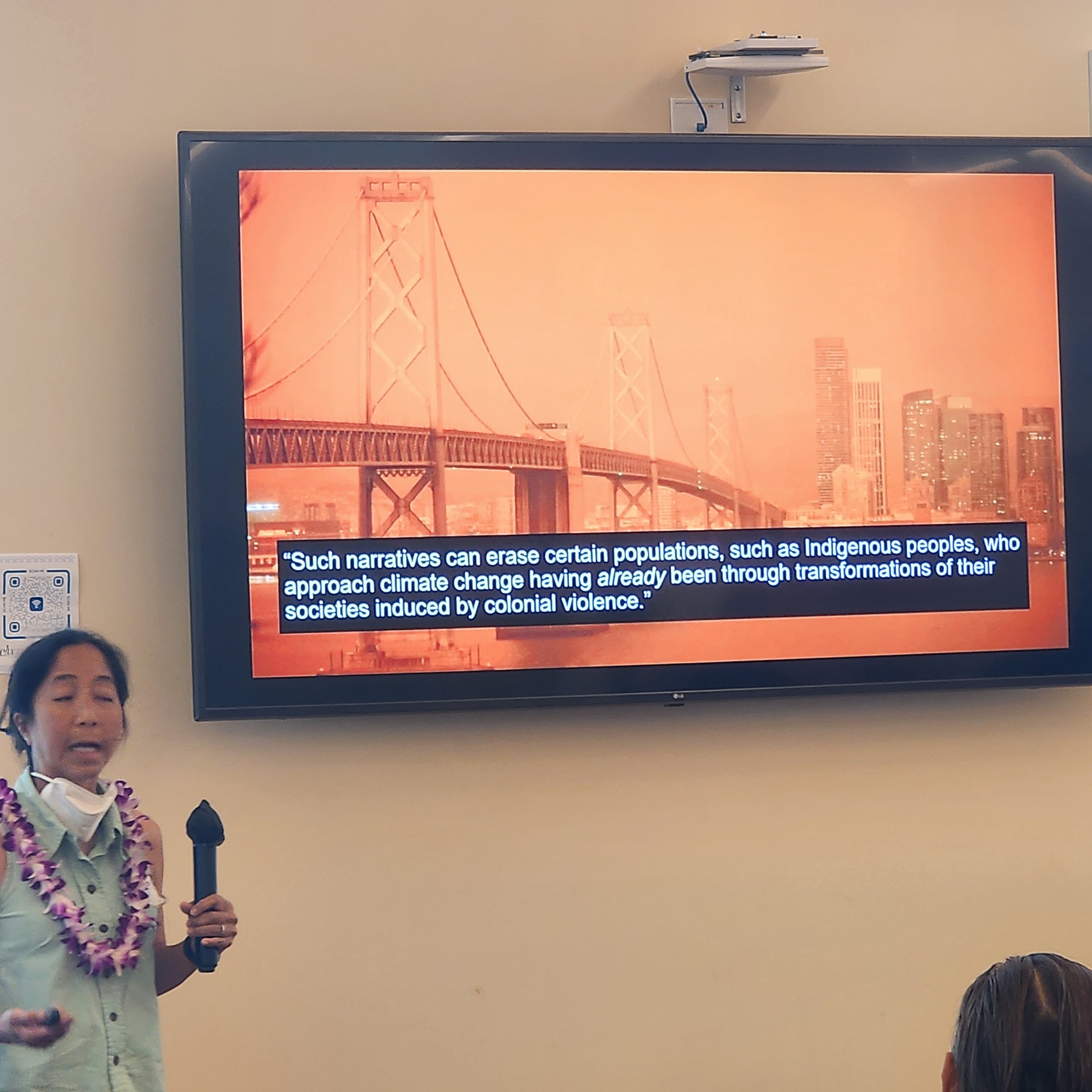

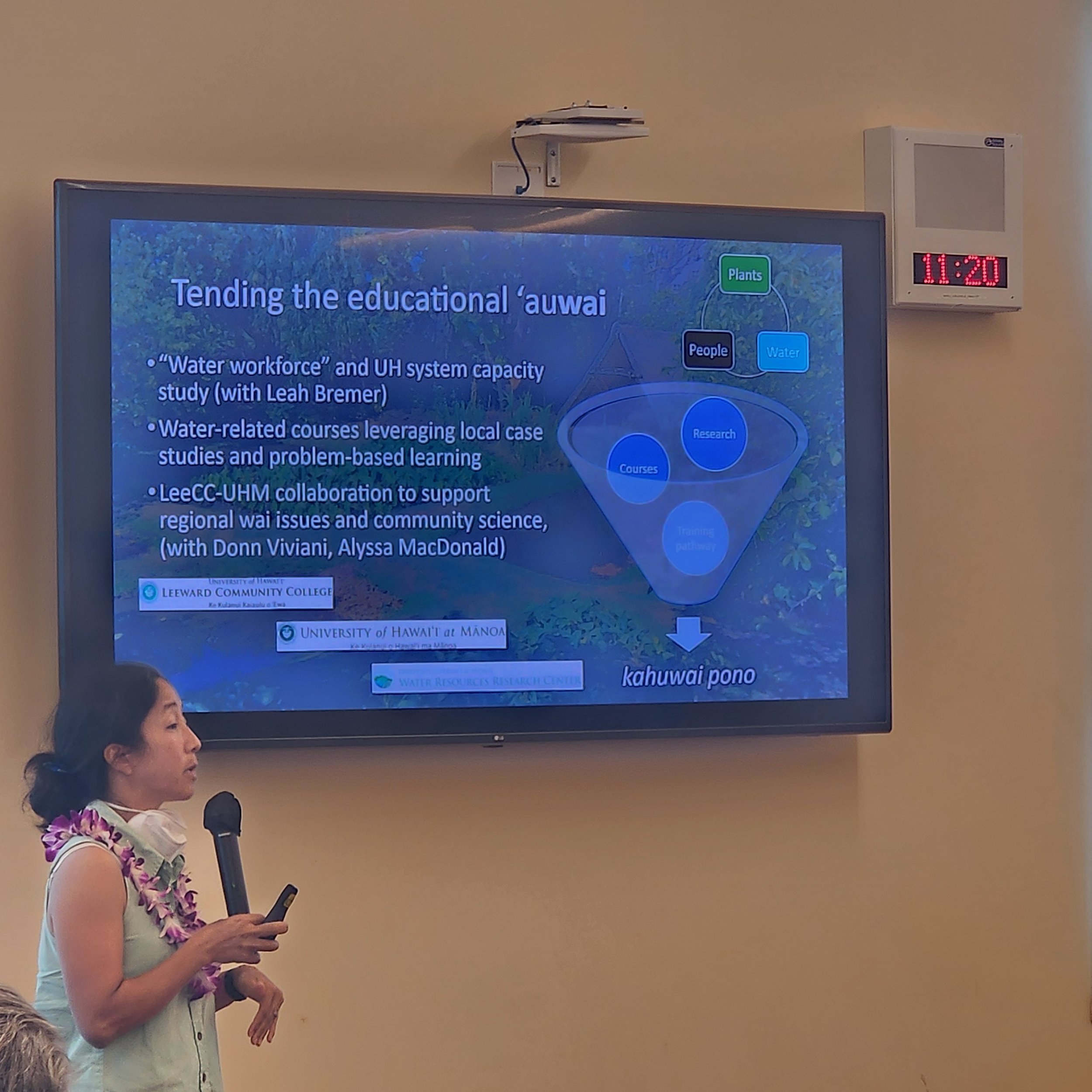

The comprehensive day-long event provided an opportunity for community members and advocates to learn the basics of water, including how we obtain our fresh wai, and to gain historical information and knowledge about the status and movement of wai in Waiʻanae. Topics covered included a “Wai 101” from state and county perspectives, which helped establish a common understanding of the impacts of climate change and rising sea levels, as well as updates on the water designation application and process. Attendees had the chance to ask questions, engage in further discussions with presenters and speakers, and participate in future hands-on huakaʻi to significant wai sites.

Two panel highlights of the day included:

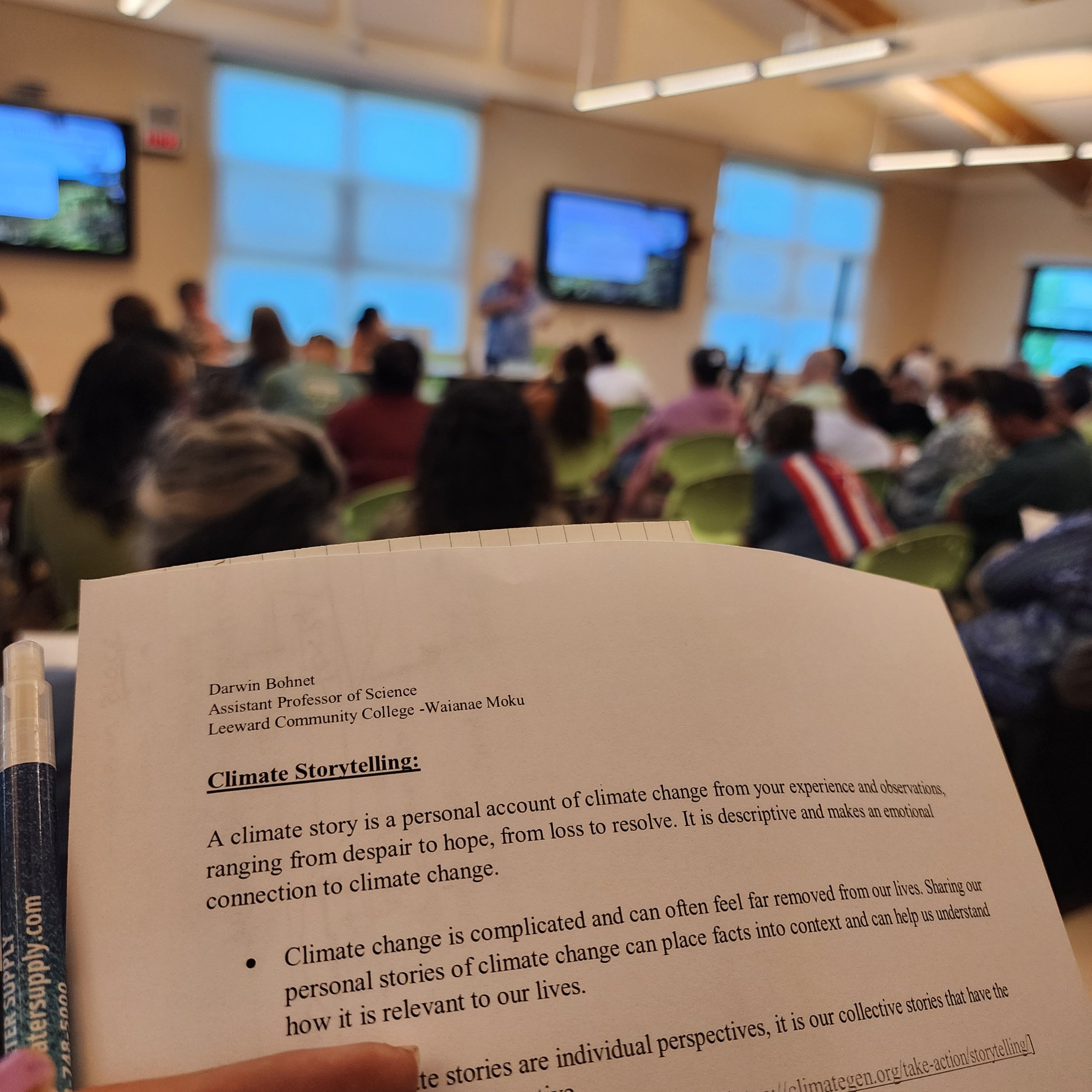

Water 101 where we were reminded that pre-contact, water was honored as a gift from akua. This perspective changed post-contact with the advent of sugar plantations, which viewed water as a commodity. Currently, 60% of Waiʻanae’s water comes from watersheds, and 40% from fog water drop-off from trees, underscoring the importance of restoring and preserving the natural ecosystems in the area. The history behind the petitioned water designation was shared, including the Board of Water Supply’s work to develop a holistic, ahupuaʻa-based approach to managing Waiʻanae’s water system, demonstrating its dedication to the physical and spiritual importance of wai. It took years for the Board of Water Supply to build trust within the community and gather manaʻo from kupuna on traditional Hawaiian water management practices. What percolated was that water was managed through cultural practices, with stewardship and kuleana deeply embedded in these practices. Therefore, including traditional practices is crucial for preserving wai in Waiʻanae and beyond.

“Careful what you throw in the ground, ends up in the water. Maybe your granddaughter’s water. But you got to be careful. A lot of us living above aquifers and don’t even know it.”- Barry Usagawa, Honolulu Board of Water Supply

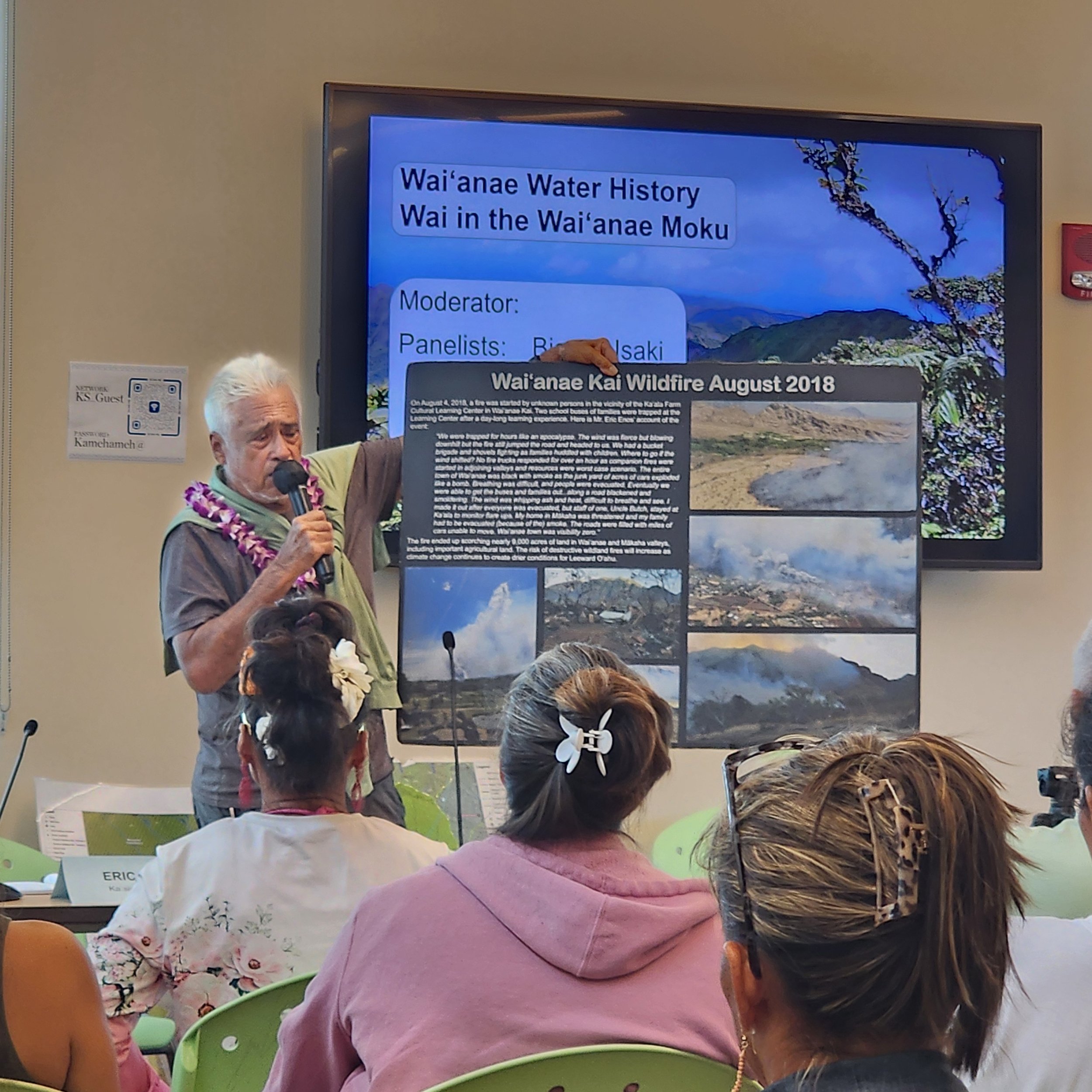

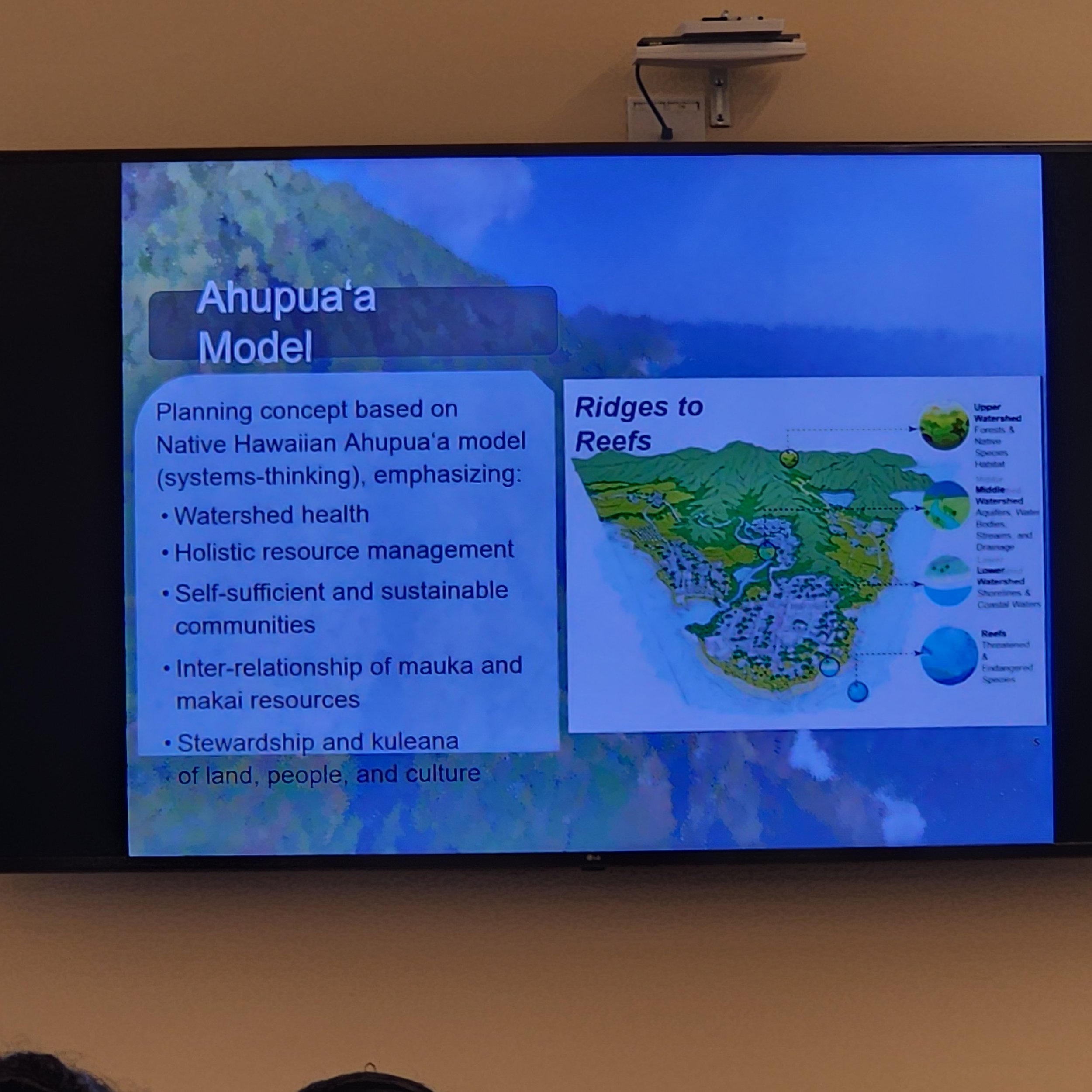

Another panel provided an overview of the historical fight for wai in the 96792 area. Bianca Isaki began with the history of settler water development starting in 1829, which initiated competition for water. Some significant milestones included: in 1880, Pennsylvania brothers drilled an astounding 700 artesian wells, prompting a small Hawaiian village to obtain a judge's order to stop them from taking more than they needed; and between 1935-1950, the Board of Water Supply began sourcing water from Pearl Harbor.

There was this and much more covered at the day-long conference. We look forward to continuing the conversation on the future of wai in Waiʻanae.

Maui Talk Story on the Grid

"The time is ripe, the time is now to take back our power," declared the event’s facilitator, setting the tone for the pivotal event organized by the Teran James Young Foundation, in partnership with the Maui Community Energy Alliance. The evening was curated to engage Maui residents in a crucial dialogue concerning the island’s energy landscape and to inspire grassroots action to control its future direction.

Panel highlights included:

Sierra Club Maui Group member Rob Weltman provided the background and intent for the talk story, emphasizing the pressing need for a safe, resilient power supply and distribution system, starting with removing electricity from the control of for-profit entities.

Sustʻāinable Molokaʻi Energy Sovereignty Organizer Leilani Chow spoke of her years of experience with the Community Energy Resilience Action Plan and the deep commitment required to ensure grassroots community voices are at the forefront of energy development. Their historically unprecedented grassroots work was grounded in exhaustive research to empower the community to understand energy rules and develop their own standards for pono energy planning, transparency, and accountability for themselves, their technical partners, and the overall Community Energy Resilience Action Plan process.

Former Commissioner Jennifer Potter provided insight on leveraging the public utilities commission for energy sovereignty such as new incentive and financing mechanisms, working with communities to create more grassroots planning opportunities, policy advocacy and more.

Maui Community Energy Alliance member Ian Hodges gave a financial overview of Hawaiian Electric, currently in junk bond status. He delivered an encouraging talk about how their vulnerability creates a significant opportunity for the community to reclaim the energy grid on Maui. Hodges suggested that a cooperative community entity might now find it easier to secure the necessary funds to buy out Hawaiian Electric. He mentioned that Kauaʻi Island Utility Cooperative became a cooperative via federal dollars when it was for sale, and speculated that while it is uncertain if Hawaiian Electric would resist or simply need the right offer, there is a path to community-owned energy or even municipal ownership, both of which benefit transparency and public participation.

Henry Curtis shared insights on the limitations of Hawaiian Electric’s regulation, noting that while Hawaiian Electric is regulated, its parent company is not. Decisions on rate designs and other matters are made behind tightly closed doors. Despite public complaints about the utility being beholden to shareholders, there is little the Public Utilities Commission can do to change that.

Why are these discussions significant?

Though water and energy conversations aren't often highlighted together unless a hydroelectric project arises and resource tensions become evident, both are deeply connected in their historical and present-day contexts. Both are declared public trust resources, preserved for the benefit of the people of Hawai'i. Both have been under attack from elite money interests, such as the corporate water theft experienced on Maui. Similarly, the privatization of energy, which should be treated as a common good, has forced many to choose between putting food on the table or paying their electricity bill.

Each is vitally critical to ensuring social equity—if people don't have access to clean, safe, and affordable water and energy in Hawaiʻi, what kind of Hawaiʻi are we living in? If we are not securing our water and resources for the next seven generations, what kind of future are we leaving to our children?

Both of these grassroots events centered around crafting a community-informed and led process for water and energy management. Although not commonly referenced, energy is held in the public trust just as water is. The priorities of communities will always be about preserving these resources for future generations, ensuring that the community always thinks beyond itself.